Name

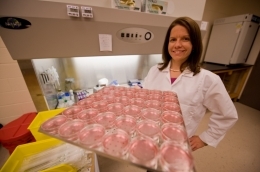

Jennifer L. Cannon, Ph.D.

Title

Assistant Professor

Institution

Center for Food Safety, Dept. of Food Science & Technology, University of Georgia

Education

B.S., Molecular Biology and Microbiology, University of Central Florida

Ph.D., Environmental Science and Technology, University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill

What early experiences influenced you to work in food safety?

During my undergraduate studies, I did an internship in a microbial water quality laboratory in Orlando, Florida. We examined bacterial and parasitic microorganisms in drinking water and reclamation water. I was inspired by and very interested in the direct application of that work. When I went to graduate school, I knew I wanted to focus on environmental virology. At the University of North Carolina, I started to focus on noroviruses, which are important waterborne contaminants and the number-one cause of foodborne illnesses in the U.S. When a position opened at the University of Georgia’s Center for Food Safety, I felt that researching noroviruses would allow me to make an impact on public health.

How did you learn about CPS?

I first heard about CPS when I started my work at the Center for Food Safety. I started looking into what CPS was about in 2009. I did not end up applying then, but in the following year we prepared a proposal for CPS.

CPS has funded “The likelihood of cross‐contamination of head lettuce by E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella and norovirus during hand harvest and recommendations for glove sanitizing and use”? Any updates?

We first gathered information about how much lettuce debris, soil, and lettuce sap accumulates on latex and nitrile gloves commonly used by head lettuce harvesting crews over time. We conducted a field study, collecting worker’s gloves at time points throughout a typical harvesting day. We thought if we collected the gloves at different times we might see differences in the accumulation levels over time, or due to the glove material. While we determine the levels of soil, lettuce debris and lettuce sap that accumulates on gloves, no significant differences between times worn or glove type were revealed. Next, we looked at the impact of lettuce sap on bacterial (E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella) and viral (norovirus) pathogen survival on gloves and found that pathogens survived longer on gloves in the presence of lettuce sap. These results are important because they suggest the simple act of rinsing gloves to remove lettuce sap can minimize pathogen survival on gloves. At this stage of the project we are investigating sanitizers typically used on gloves. We have compared rinsing with chlorinated water, water alone, and rinsing with a novel levulinic acid plus SDS sanitizer for inactivating E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella and noroviruses on latex and nitrile gloves. Across the board, levulinic acid with SDS did out-compete the chlorine sanitizer and of course water, but we found some interesting results. We are finding that with each sanitizer there is sometimes incomplete pathogen inactivation. We think that some glove materials can be protective towards pathogens that are on the gloves. We are now focusing on finding the right combination of sanitizer treatment and glove material that will result in the greatest level of pathogen inactivation.

What do you think the industry will gain from your research project?

Our goal is to be able to make recommendations on glove types and glove sanitation procedures that will improve the safety of leafy greens during field harvest. We are primarily focused on finding interventions that would not cost much money and would be easy for industry to put into practice.

Where do you see food safety in five years down the road? Why?

The Food Safety Modernization Act will bring a lot of attention to this field. It is good business to give consumers a safe product. I am hoping that funding of applied projects through the Center for Produce Safety and the USDA NIFA program will result in scientific backing to some of the recommendations that have been made for preventative control.

What does a normal day consist of?

I don’t really have “normal” days. On some days I get to the lab and have one-on-one experiences with my technicians and students. I really enjoy that. I enjoy getting to see them develop and aiding them in reaching their goals. I have students in the lab that are working on their Masters and PhDs. I have two labs, one in Griffin, Georgia, which is my main lab, and one on the main campus at UGA. This keeps me busy! Any extra time I do have, I am performing data analysis and writing papers.

What are your interests?

Most of my focus has been on foodborne viruses. I am looking into novel methods of detection, pathogen persistence in the environment, and strategies for prevention and control. An interest that I have outside of food safety is native microbial flora within the gut. The fact that there are more microorganisms in and on our bodies than there are of our own cells within our bodies is fascinating. I also enjoy mountain biking, yoga, and capoeira (a Brazilian martial art).

Please describe one or more of your career highlights.

One career highlight is getting to work with and collaborate with individuals from a variety of backgrounds at the Center for Food Safety, at the University of Georgia, and with Georgia collaborators at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Emory, and the CDC. I have also been lucky to be a part of a foodborne virus initiative funded by the USDA-NIFA and led by Lee-Ann Jaykus at North Carolina State University. We are all working together to come up with solutions for better detection, prevention, and control of foodborne viruses, with a focus on human norovirus.